On April 21st, 1945, forces of the First Belorussian Front under Marshal of the Soviet Union Georgy Zhukov broke through the shattered defenses of the German 9th Army under General Theodor Busse at Seelow Heights, the last defensive line between the onslaught of the Red Army and Berlin, the dark heart of the Reich, which lay just 56 miles away. On April 22nd the first Russian troops entered the city, and by the 23rd, it had been completely surrounded, with nearly two million Russian troops flooding into its streets. The battle had begun, and within two weeks, Hitler would be dead. Yet the defeat of the Reich lay not in Hitler’s inability to control the massive Red Army, but his inherent inability to both accept defeat as well as overcome. Hitler could not accept reality, and as the war came to Germany’s doorstep, the casualties only mounted. By war’s end, between 50 and 70 million people lay dead, 25 million of them civilians. 20 of Hitler’s infantry and armored divisions were facing the Western Allies along the river Rhine, while in the east, 235 were facing the Red Army, a force that towered over the bewildered, horribly outnumbered, and outgunned Wehrmacht, who had sworn an oath to Hitler to defend the dying Reich to the last man, the last bullet, the last breath.

On June 6th, 1944, between 150 and 170,000 British, Canadian, and American troops waded ashore off the coast of Normandy, a region on the northern coast of the larger Contentin Peninsula. Hours prior to their landing, 13,600 British and American paratroopers landed behind enemy lines to disrupt communications and supply of reinforcements, as well as secure pathways for the landing infantry to move inland. With the five beachheads–Utah, Omaha, Gold, Juno, Sword–secure by the end of the 6th, and with infantry moving inland after thwarting several small scale counterattacks, namely at Sword Beach in the evening of the 6th, the war had been brought to the threshold of Fortress Europe (see: the Fall of the Third Reich: From D-Day to the Rhine). Just one day prior to the Allied landings in Normandy, advanced forces of General Mark Clark’s 5th Army had reached Rome to celebrating and joyous crowds, just days following a breakout from Monte Cassino and Anzio, two hard-fought battles that had cost the Allies nearly five months of invaluable momentum. They were nearly halfway up the Italian peninsula, and by spring 1945, Allied forces would reach the expanses of the river Po, the last defensive line before the daunting snow-capped peaks of the Alps, as well as the bustling metropolises of Milan, Genoa, and Venice. Rome was the first Axis capital to fall, and within eleven months, Berlin would join it. As Clark’s 5th Army advanced north along Italy’s western coast, with General Oliver Leese’s British 8th Army advancing along the eastern coast in tandem, Allied forces stormed ashore at Normandy, breaching the vaunted Atlantic Wall, and pouring into the formidable bocage, farm fields and chateaus divided by hedgerows, massive walls of ancient roots and foliage that in some cases grew several feet high. The territory favored the defenders, and as American forces advanced in the direction of Saint-Lo, the designated target for their breakout, they ran into considerable resistance from determined German defenders, in some cases men of the zealous Waffen-SS and elite Fallschirmjaeger paratroopers. Following a somewhat belated victory at Cherbourg in late June, one in which Allied commanders felt no need to celebrate due to the port’s almost complete destruction at the hands of stout German defenders, American forces under General Omar Bradley advanced to Saint-Lo, through a pathway opened by the British at Caen. Field Marshall Bernard Montgomery, the outspoken, repugnant hero of El Alamein in November 1942, had opened a window for Bradley’s troops to pour into the bocage, even if it was at the cost of momentum in taking his overall target, the massive ancient Norman city of Caen. Hitler’s inability to comprehend the gravity of the situation, compounded with his being duped by the notorious Double Cross system utilized by British and American intelligence agencies for feeding the Germans false intelligence while simultaneously gaining correct intelligence from the opposite end, allowed American forces to combat their way deep into the bocage against relatively light resistance, in comparison to that facing the British under Montgomery.

When British and Canadian forces waded ashore at Gold, Sword, and Juno Beaches, they were under orders to capture the city of Caen on the first day of offensive action, yet an unexpected German counterattack spearheaded by armor of the Waffen-SS late in the afternoon of the 6th threatened to toss those landings back into the sea, and was only thwarted by British air and naval supremacy and overwhelming firepower. With the considerable loss of momentum on the first day of offensive action, Montgomery never fully recovered, and attempted to breach the city’s formidable defenses time and again, only to be continually thrown back by superior German firepower. With his men outnumbered and outgunned, Montgomery broke into Caen in July after Allied bombing raids destroyed nearly half the city, killing thousands of civilian inhabitants caught in the deadly crossfire. The city was not taken until August 6th, 1944, two months after it was designated to be seized, yet in Montgomery taking considerable time and casualties, he inadvertently drew massive amounts of German armor stationed at the Pas-de-Calais away from hampering the sluggish advance of General Bradley to the south. By late July, after considerable bombing raids that not only killed German yet also American forces, including the highest ranking American soldier to be killed in combat, Lieutenant General Lesley McNair, Bradley broke out during Operation Cobra, his armor pouring through the gap blasted into German lines at Saint-Lo. Almost simultaneously, Montgomery seized Caen, moving southeast toward Bradley, encircling Field Marshall Gunther von Kluge’s Army Group B between the Norman towns of Falaise and Chambois, the with the pocket closing, the two Allied armies threatened to cut off von Kluge’s beleaguered men, numbering almost 100,000 men. From August 12th to the 21st, 1944, von Kluge’s Army Group B, surrounded on three sides by two British and American army groups, locked itself into a death grip with the Allied armies, fighting tooth and nail to avoid not only utter destruction but also to secure an escape route, a small opening in the almost perfect pocket the two conjoined Allied army groups created. This pocket near the town of Falaise, from which the infamous, gruesome nine-day battle took its name, offered the only viable escape route for von Kluge and his men, and, if exploited, could allow him to send what was left of his army group across the river Seine to the comparative safety of northern France and Belgium, and allow them to fall back to the river Rhine and defend the Reich’s doorstep. By August 21st, the surviving 40,000 men of von Kluge’s annihilated Army Group B fell back across the Seine, leaving behind 60,000 dead, including von Kluge, who had committed suicide on the 17th, being replaced by Field Marshall Walter Model. Von Kluge had realized his failure not only to save his men, yet also his failure to defend the Reich, and compounded by his fears that his involvement in the July 20th plot to assassinate Hitler had been exposed with Hitler recalling him to Berlin, he had prompted himself to commit suicide with cyanide. Yet before von Kluge poisoned himself while returning to Berlin to consult with Hitler, he authored a letter strongly advising Hitler to end the war, cautioning him that his failure to do so would lead to the annihilation of Germany. Hitler commented upon reading it that regardless of his involvement in the July 20th plot, von Kluge would have been arrested anyway. On August 25th, with Army Group B almost completely destroyed and retreating across the Seine toward Germany, Allied forces under General George Patton advanced into Paris after General Dietrich von Choltitz disobeyed a direct order by Hitler to burn the city to the ground. By early September, Allied forces had poured into France against nearly no resistance, with the majority of German defenders having fallen back to predesignated defensive positions along the stretches of the river Rhine, and on September 17th, 1944, with the positions of the British 2nd Army under General Miles Dempsey consolidated in Belgium, the Canadian 1st Army under General Harry Crerar clearing the Scheldt Estuary after seizing the port of Antwerp, and with the American 3rd and 1st Armies under Generals George Patton and Courtney Hodges consolidated along the German frontier, with Patton’s forces moving into the Huertgen Forest near the city of Aachen in mid-October, Allied forces launched a daring assault into the Netherlands that possessed a fifty-fifty shot at failure or success.

The plan was code-named Operation Market Garden, with the objective of dropping 40,000 British, American, and Polish paratroopers along a stretch of highway in the southeastern Netherlands between the cities of Eindhoven, six miles from the Belgian frontier, and Arnhem, sixty miles from Belgium. Highway 69, the stretch of road between Eindhoven and Arnhem, possessed eight bridges over the Dommel, Wilhelmina, Meuse, north Rhine, and Waal canals, with a bridge at Eindhoven, one at Sint-Oedenrode, one at Veghel, two at Son, one at Grave, one at Nijmegen, and one at Arnhem. All eight needed to be seized to allow British armor of General Brian Horrocks’s XXX Corps, spearheaded by the Guards Armored Division, to advance north along Highway 69, swing around the formidable defenses of Siegfried Line, a massive defensive line stretching along the entire length of Germany’s western border, advance unhampered along the flat North German Plain, and enter Berlin, negotiating a surrender, optimistically, by Christmas 1944. The plan was audacious and a gamble at best, yet with no functioning ports in Allied hands, safe for Antwerp and Cherbourg, seized in June and September respectively, which were almost completely useless, it had to be taken. Antwerp could not be utilized until the Scheldt Estuary, a river running inland from the North Sea to the port inside Belgium, could be opened by the Canadians under Crerar, and Cherbourg still needed massive amounts of repairs in order to completely refit it into a functioning port. The only port in Allied hands was Marseilles, on France’s Mediterranean coast, seized by General Jacob Devers’s 6th Army Group when American and Free French forces stormed ashore between Nice and Toulon during Operation Anvil-Dragoon on August 15th. Marseilles was far too distant from the front lines, and when the two artificial Mulberry ports, two massive piers jutting out into the deep water of the English Channel, were destroyed in a storm, all Allied supplies had to be landed directly on the original invasion beaches, and soon, the roads running inland became choked with traffic. Immense amounts of Allied bombing prior to the D-Day landings on June 6th had destroyed the majority of roads and railway systems running inland, and crisscrossing throughout Normandy, and much of the rest of France. The idea of the bombing was to limit the ability of Germany to bring reinforcements to bear against the landings, as well as hamper their ability to move about supplies. It had worked against the Germans, and now was now working against the Allies, forcing them to truck supplies directly from the choked invasion beaches all the way to the front lines, which, with the bewildered German forces falling back as quickly as they were, moved on almost a daily basis. This prompted the construction of the Red Ball Express, a system of trucking supplies from the D-Day beaches to the ever-changing front lines, most notably those within the jurisdiction of General Patton. The system was run primarily by black drivers, and worked successfully for quite some time following the breakout from Saint-Lo all the way to the first American troops seeing the Rhine in October, yet Eisenhower was being faced with a serious problem at Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force. With the ever-present issue of supply and who gets what, Eisenhower was faced with a decision to give priority supply to just one of his generals, and, as it was in most cases, his choices were narrowed down to Patton and Montgomery, who, ironically, hated each other ever since Sicily. Since Operation Husky in July 1943, in which Patton unexpectedly turned west and captured Palermo before turning east and taking Messina instead of staying with Montgomery and protecting his left flank as he advanced northward along Sicily’s east coast to take Messina and stop a potential German withdrawal to the Italian mainland, the two had been at odds, with both wanting to seize the glory. Their rivalry had not started in Sicily–it had actually begun in Africa–but it had come to a head in Sicily, and now that rivalry was resurfacing in who would be given the offensive flexibility to enter Germany and be the first to end the war. Montgomery proposed Operation Market Garden, a large scale, the largest ever attempted, airborne drop into the Netherlands to outflank the Siegfried Line with the prospect of ending the war by Christmas, with Patton proposing a limited amphibious landing across the Rhine to seize Mainz, Koblenz, and Mannheim in Germany, scoring several bridgeheads across the river that could potentially be exploited, widened, and crossed by divisions at a time. The more audacious plan won the day, and on September 10th, Eisenhower approved Market Garden. If successful, not only would the drops secure a foothold in the Netherlands and outflank the Siegfried Line, it would also trap the German 15th Army in the western Netherlands, forcing its back to the North Sea. On September 17th, 1944, around 1:30 p.m, the first British and American paratroopers fell from the sky over the Netherlands. Almost instantly the plan went awry. British radios had been issued with the wrong batteries and communications were impossible, American paratroopers of the 82nd Airborne Division were ordered to consolidate their positions around Nijmegen instead of pushing to take the 2,000-foot road bridge that same day, which cost them several days of valuable momentum, British armor of XXX Corps had been stalled almost instantly due to heavy German resistance in the woods alongside the highway leading to Eindhoven, and one of the two bridges at Son had been destroyed. The British were forced to repair the bridge at Son utilizing a Bailey bridge, with them already being nearly a day and half behind, with Market Garden, on paper, supposed to take only two days to complete. The 82nd Airborne soon attempted to take the bridge at Nijmegen, yet ran into nearly a regiment’s worth of SS infantry. Had they attempted to take the bridge the day they landed, they would have been up against twelve men. The British around Arnhem had landed near the residential area of Oosterbeek, and soon, overwhelming German armor of General Wilhelm Bittrich’s 2nd SS Panzer Division Das Reich surrounded them, pushing them into a narrow pocket with their backs to the North Rhine Canal, and forcing them away from their original drop zones. With Bittrich’s men surrounding the British at Oosterbeek, and with communications nonexistent due to faulty radios, Polish paratroopers under General Stanislaw Sosabowski were dropped into the fight to bolster the strength of the bewildered British 1st Airborne. Unbeknownst to Sosabowski or his men, the Germans had overrun the drop zones, and when the Polish landed, in broad daylight, many were gunned down before they ever reached the ground. Similarly, the British 1st Airborne’s being forced into a pocket at Oosterbeek also cut off Colonel John Frost, who had been ordered to push into Arnhem on the first day to take the city’s 2,000-foot road bridge. Frost fought with vigor, yet was forced to surrender just days into the fight due to the introduction of German armor, which his men had not been equipped to fight. With American forces having secured each of their seven bridges at Eindhoven, Veghel, Son, Sint-Oedenrode, Grave, and Nijmegen, and withstanding several counterattacks by determined German troops on either side, with men of the 15th Army attacking in the west and men from the Siegfried Line attacking from the east, it was finally realized that Market Garden had failed, and on September 25th, 1944, it was announced that Market Garden had been a “90 percent” success. And with that, the war became relatively quiet in the west, with Allied forces digging in along the west bank of the river Rhine for the oncoming winter, and with the Scheldt Estuary being taken in November, supplies began to flow to the front lines, yet at first it was just a mere trickle. The fighting at Aachen and in the Huertgen Forest, which had commenced in September, would pour over into the winter of 1944, and well into February 1945, yet the real fight was coming, a bulge of German armor looming over the horizon.

On July 20th, 1944, Colonel Claus von Stauffenberg, a relatively unknown German officer of aristocratic blood deployed to Tunisia in 1943, where he suffered the loss of his left eye, hand, and three fingers on his right hand, detonated an explosive device at Hitler’s headquarters at Rastenburg, East Prussia. Almost immediately after, he was flown back to Berlin, where he, and many others, including Generals Friedrich Olbricht and Henning von Tresckow, attempted to seize power. They were under the misconception that Hitler had been killed in the blast, although he had suffered mere cuts and bruises, and within hours, the conspirators were rounded up and either executed immediately, or tried by the corrupt People’s Court of Judge Roland Freisler, and either sentenced to execution or life in prison. The plot to kill Hitler on July 20th, code named Operation Valkyrie, was one of forty two attempts on the Fuehrer‘s life, and the only one that came close, if not briefly touched, success. It had been the product of several years of careful planning by members of Hitler’s military staff, and had become known by several high ranking military officers, yet, like the killing of Julius Caesar in 44 B.C, those who possessed knowledge did nothing to stop it, and they were later hunted down and executed for their alleged involvement, including Field Marshall Erwin Rommel, who was given the option of committing suicide by cyanide with the understanding that his death by his own hand for his involvement (although he only knew about it), would keep Hitler’s Germany from interfering in the lives of his wife and children. Field Marshall Gunther von Kluge committed suicide in a similar fashion, although he was actually completely unaware that his knowledge of the attempt had been exposed when he was summoned back to Berlin. Operation Valkyrie had originally been drafted as a contingency plan to utilize the Territorial Reserve Army if there was internal strife due to the sheer weight of Allied bombing raids or an attempted coup, but was changed under the direction of Claus von Stauffenberg after he was promoted to chief of staff of the Territorial Reserve Army to also compensate for internal coup d’etats, as well as drafting an emergency continuity of the government in the event Hitler himself was killed or incapacitated. The plan was put into effect after Stauffenberg visited Hitler’s Rastenburg headquarters, die Wolfsschanze, the Wolf’s Lair. Originally, it had been planned to detonate the explosives in the command bunker, which possessed walls some three meters thick of steel reinforced concrete. The massive pressure change caused by the blast would have killed anyone inside, regardless of their proximity to the explosion, yet on July 20th, it was too hot in Rastenburg, and so they opted to change the location of the meeting to a nearby conference hut with open windows, which would allow the blast room to exit, dampening its potential effectiveness. After the blast, Stauffenberg flew back to Berlin to assume command of the new Germany, yet within hours, it was discovered Hitler was still alive, safe for some minor injuries, and those SS officials captured by the Territorial Reserve Army after Stauffenberg claimed they were attempting to seize power, were released, and the Territorial Reserve Army was ordered instead to capture or kill Stauffenberg and those working alongside him. This attempt on Hitler’s life struck a particularly resounding chord with Hitler, as it had been committed by his own army, men who had sworn an oath of loyalty to him, and for the remainder of the war, he trusted very few, and those who betrayed him, or he felt may have betrayed him, were executed in the most gruesome of fashions. While Hitler recuperated in hospital following the near-fatal blast (it had only been stopped from killing Hitler when Colonel Heinz Brandt moved the briefcase containing the explosive behind a table leg that would absorb the blast, but in doing so sever both of Brandt’s legs. He had done it because he wanted to get a closer look at the map table, not because he knew the bomb was in the briefcase), he drew up what became known as Operation Watch on the Rhine, a daring offensive that was to be launched as a three-pronged assault deep into the Ardennes Forest, a relatively under-defended portion of the Allied lines, with the objective of ripping a hole in the American lines, advancing to the port of Antwerp, seizing it, and then turning south, utilizing their offensive momentum to drive south and seize the river Meuse before negotiating a peace with the Allies after splitting Field Marshall Bernard Montgomery’s 21st Army Group in Belgium and the Netherlands from General Omar Bradley’s 12th Army Group in southern Belgium, Luxembourg, and northern France. It would become known as the infamous Battle of the Bulge.

With fighting dying down in the Huertgen Forest and the Netherlands, with Antwerp secured, the Western Front seemed quiet. From late November to early December, very little was happening, yet on the night of December 16th, 1944, the tentative peace was shattered. German forces of the Waffen-SS and newly created Volkssturm, formed in October 1944 to recruit men between the ages of 16 and 60 to defend the Reich, poured inexorably into Belgium and Luxembourg, with men of the 6th SS Panzer Army under General Sepp Dietrich assaulting the Losheim Gap and the defending Elsenborn Ridge to reach the crossroads town of Liege, while men under the command of General Hasso von Manteuffel stormed through the forest, decimating the 28th Infantry Division, which had been dispatched to the Ardennes after nearly a month and a half of combat in the Huertgen Forest to rest and recuperate. The Division fell back to Neufchateau on December 22nd after making contact with Manteuffel’s 5th Panzer Army, stalling the German advance in the center, throwing off the German timetable, and buying considerable time to allow the 101st Airborne Division to be trucked to the crossroads town of Bastogne after several weeks of rest at Mourmelon-le-Grand. To the south, General Erich Brandenburger’s 7th Panzer Army attempted to move into Luxembourg and secure the southern flank of the advance, yet within days, insurmountable problems surfaced. The advance north under Dietrich stalled, with men of the 1st Infantry Division moving in from fighting in Aachen to hold Elsenborn Ridge, which commanded Losheim Gap, the only realistic route to Liege. Without taking Liege, the German advance would be forced to advance without a northern flank, threatening Manteuffel’s 5th Panzer Army to be overtaken by Field Marshall Bernard Montgomery’s 21st Army Group in Belgium and the Netherlands. In the center, the 28th Infantry Division’s gamble of falling back to Neufchateau to buy the 101st time to consolidate a defense of Bastogne paid off, and when Manteuffel’s tanks fell upon the crossroads town, they came under fire from the men of the 101st, prompting Manteuffel to attempt a siege, costing the offensive the whole of its valuable momentum, and killing its ability to reach the Meuse and Antwerp. By late December, it had become obvious that the offensive was dying, and on New Year’s Day 1945, Patton’s 3rd Army broke through, surrounding those surrounding Bastogne, and forcing the German offensive to fall back to the Siegfried Line or face annihilation at the hands of Patton. As it appeared the offensive had died, Hitler drafted Reichsmarschall der Schutzstaffeln Heinrich Himmler, a personal favorite of Hitler’s, to launch an assault against American positions in Alsace-Lorraine in the northeastern France. Operation North Wind, as it came to be known, was the last large scale German offensive launched against the Western Allies, and by early February, it had appeared it had failed as well, with the embattled 101st Airborne moving south to assist the 7th Army under General Alexander Patch in holding the town of Haguenau. With the German offensives thrown back with severe casualties, and with offensive mobility once again handed back to the Western Allies, between the months of February and March, the British 21st Army Group under Montgomery, consisting of Miles Dempsey’s British 2nd Army, William Simpson’s U.S. 9th Army, and Harry Crerar’s Canadian 1st Army, launched Operations Veritable, Grenade, and Blackcock, and with the American 12th Army Group under Bradley, consisting of the U.S. 1st Army under Courtney Hodges, 3rd Army under Patton, and 15th Army under General Leonard Gerow, launched Operations Lumberjack and Queen, while the American 6th Army Group under Jacob Devers in southern France, near the Swiss border, consisting of the U.S. 7th Army under Alexander Patch and French 1st Army under Jean de Lattre de Tassigny, consolidated their position in the south. It was part of Eisenhower’s “broad front strategy”, in which the Allied armies would secure everything west of the river Rhine before attempting a large-scale crossing (Allied forces had already gone inside Germany, with the first German city, Aachen, falling into American hands in late October 1944, and as early as September of that year, American forces under Patton were already in sight of the Rhine), and by late March, a large scale crossing in both north and south was underway, with Patton crossing over the Ludendorff Bridge in the town of Remagen, the only bridge still standing over the Rhine that had not been blown by retreating German troops, and with British forces crossing near Rees and Wesel during Operation Plunder, along with the airborne element of Operation Varsity. By late April 1945, American and British forces had surrounded the Ruhr Pocket, the industrial heart of Germany, and by May, the 6th Army Group under Devers had linked up with the 5th Army under Mark Clark in the Brenner Pass in the Austrian Alps, the British had taken Hamburg, and American forces had Torgau, on the river Elbe. Yet in the east, the fighting was far from organized, and the Russians were aiming to exact a terrible revenge on the man who had not only started this terrible war, yet had dragged the Soviet Union down into its hellish flames.

By May 1945, men of the Russian Red Army had taken East Prussia, Poland, Yugoslavia, Romania, Czechoslovakia, Finland, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania, Belorussia, the Ukraine, the majority of Hungary, and were advancing into the southern and eastern regions of Germany and eastern Austria, toward Vienna. Since February 1943, when Field Marshall Friedrich Paulus’s 6th Army was annihilated at Stalingrad, offensive capability had been soundly handed to the Red Army. The strategic reverses of 1941 and early 1942, including the loss of Smolensk, Kursk, Kharkov, Kiev, Vitebsk, Rostov, Orel, and the surrounding of Leningrad, had been overcome, and the Red Army had been handed the offensive capability it had so long desired. The victory at Stalingrad had been a resounding victory not only for sparing the cities of Grozny and Baku from falling into German hands, yet also decimating Germany’s ability to counter the Red Army’s inexorable force. Outnumbering and outgunning the forces of the Wehrmacht, the Red Army began to steamroll over them, taking Kharkov, the third largest city in the Soviet Union, back in March 1943 following their coup at Stalingrad. The majority of the liquidity of the Russian war in 1943-44 was fought in the south, primarily in the Ukraine, yet soon began to bleed over into the center and north, with the siege of Leningrad being lifted in late 1944 after nearly three years. The German army in the center had been holding the very same defensive position it had clung to following the success of the Russian counterattack that drove them back from Moscow in December 1941, yet following the defeat at Stalingrad in February 1943, the capture of Kharkov in March 1943, and the Russian victory at Kursk in July 1943, in which a German counterattack consisting of 900,000 men commanded by Field Marshall Erich von Manstein, often regarded as the most talented tactician of the 20th Century, was thwarted by nearly 2 million Red Army soldiers near the city of Kursk and the neighboring town of Prokhorovka, where the largest tank battle of the Second World War occurred. By the winter of 1943, the Wehrmacht had been driven nearly across the whole of the Ukraine, the last bastion of German resistance before Romania, Yugoslavia, Czechoslovakia, and southern Germany, trapping the 5th SS Panzer Division Wiking in a pocket near Cherkassy in January 1944 due to their inexorable speed and sheer size. To the north, the Red Army was systematically breaking the resistance of Army Groups North and Center, driving North back into the Baltic States and Center toward the Polish frontier by the spring of 1944. The Red Army’s immense size, coupled with outstanding leadership, such as Georgy Zhukov and Konstantin Rokossovsky, allowed for it to steamroll over the Wehrmacht, which, in some cases, the Red Army outnumbered ten to one. The German military had suffered a staggering defeat in February 1943 that it did not fully recover from, and in that defeat the Russians were quick to capitalize, throwing masses of infantry against beleaguered German troops they did not give the proper time to rest and recuperate from previous defeats. The rapid advance of the Red Army following Stalingrad swallowed Kharkov, Kiev, lifted the siege of Sevastopol, orchestrated by Field Marshall Erich von Manstein and utilizing on of the largest siege cannon ever constructing, the 800mm Schwerer Gustav (Gustav’s sister, Dora, was commissioned by the Wehrmacht as well to be utilized to shell Stalingrad in the winter of 1942, but she was not brought to bear and later sabotaged to prevent her capture. Hitler had an affinity for big guns, and this much is obvious not only during the siege of Sevastopol yet also in the siege of Anzio from January to May 1944, in which the Wehrmacht utilized two 283mm Krupp K5 siege cannon, known as Anzio Annie and Anzio Express. Three K5’s were also placed in northern France to target British shipping in the English Channel, and one actually succeeding in sinking a British ship). The Red Army’s advanced lagged slightly in the summer of 1943 around the city of Kursk, granting the Wehrmacht‘s bewildered Army Group South a grace period to attempt offensive operations, and this came in the form of Operation Citadel, a last-ditch effort to cut off the abscess of a Russian salient bulging into German lines near Kursk, yet the offensive failed, and offensive flexibility was essentially handed back to the Red Army. By summer 1944, the Red Army sat poised to enter Poland, as well as breakout of the Ukraine and flush southward into Romania, a German ally and the leading exporter of oil to Germany, Yugoslavia, and Hungary, another German ally. These breakouts came in the forms of the joint Operation Bagration and the Lvov-Sandomierz Offensive, launched in late June and mid-July 1944 respectively. They coincided directly with the D-Day landings in Normandy, and were designed to pinch the German military on two fronts, and force them to combat two very real threats to the Reich. The Wehrmacht had executed a rather disorganized retreat back to the Polish frontier, and they were shambles. Another offensive could threaten the structural integrity of the German army in the East, and, if successful, could threaten Germany. Opening up on June 22nd, 1944, with a massive barrage and infantry assault near Vitebsk-Orsha, Operation Bagration would advance to Osowiec, in central Poland, as well as advancing into the Baltic States and eastern East Prussia. By the end of Bagration on August 19th, 1944, Army Group Center ceased to exist, and three of its armies, the 9th Army, 4th Army, and 3rd Panzer Army, were annihilated. What was left fell back into western Poland, preparing itself to defend the Reich itself. Army Group South, renamed Army Group A, was forced from the southern Ukraine and Poland by the Lvov-Sandomierz Offensive, which opened a pathway straight into Yugoslavia, Romania, and Hungary. The shattered remains of Army Group A fell back to defensive positions within those respective countries, and by early September, the Red Army was attempting to breach the defenses in the Carpathian Mountains, launching the dual Jassy-Kishinev Offensives, the first failing yet the second achieving success. The success of the Jassy-Kishinev Offensive prompted King Michael, the true monarch of the Romanian thrown, to execute a coup d’etat, and seize his power back. He had been removed from said authority in the early years of the war due to his opposition to Fascism and the Nazi Party, yet many in his inner circle thought otherwise, and in September 1944, he took the throne that was rightfully his, surrendering Romania, and within days, joining the Allies and declaring war on Germany. The loss of Romania struck a deep chord with Germany because not only had Romania been an ally that had committed troops to assisting in the defense of the Reich, it had also been Germany’s leading supplier of petroleum, which Germany’s panzers were already running low on. With Romania out of the war, Germany’s meager petroleum reserves, which were being targeted almost daily by Allied day and night bombing, could not sustain the German military for long. The Red Army utilized Romania as a springboard, and shifted their attention south, to Yugoslavia. The Kingdom of Yugoslavia had been created in 1918 in the aftermath of the First World War, and when the Kingdom was shattered by Germany’s April 1941 Operation Punishment, the ethnic, religious, and politic tensions and rivalries that had been so common in the area, yet had been suppressed for so long, exploded, and allowed three political movements to took root: the Communists under Josip Broz, or Marshall Tito, the monarchist Chetniks under the command of Colonel Draza Mihailovic, and the Fascist, collaborationist Ustase under Ante Pavelic. Originally, the Ustase had been the only group inside the dissolved Yugoslavia to cooperate with the German occupiers, evening constructing their own concentration camp, Jasenovac, to assist in Germany’s campaign of genocide. The British, who had taken quite an interest in the events unfurling in the Balkans, had dispatched men of the Special Operations Executive to Yugoslavia, primarily to Serbia, where the Chetniks operated, to work with Mihailovic and his men, who were waging a guerrilla war against the German occupiers, yet it was soon discovered that the Chetniks were receiving aid from Nazi Germany, and were actively cooperating in anti-partisan activity, with the Germans capitalizing on the Chetniks’ hatred for Tito and his Communists. With the Chetniks and the Ustase actively supporting the German military in their campaign to wipe out any partisan activity in Yugoslavia, the British were forced to turn to Tito, a man they had not been willing to support up to that point. Josip Broz had been a high ranking member of the Royal Yugoslav Army prior to the outbreak of war and the German invasion in April 1941, and his actions regarding Yugoslavia’s tentative, albeit short-lived, allegiance with Nazi Germany would lead to the invasion. Yugoslavia had been an original signatory of the Tripartite Pact, binding it to Germany in alliance, yet Tito and several others led a coup d’etat that overthrew the government and pulled Yugoslavia from the Pact, prompting a German invasion. Following the invasion, Tito and his Communists had been forced into a tiny pocket in northwestern Bosnia, where they launched the majority of their guerrilla campaigns against the German occupiers, considering Serbia, which included Serbia and Montenegro, was controlled by the Chetniks and Croatia by the Ustase. The British had originally been unwilling to support Tito and his men due to their Communist affiliation, yet following the betrayal of the Chetniks, they were the only viable option left. And that was how the situation remained when Red Army forces entered Yugoslavia in October 1944. Prior to the Russian invasion, the Wehrmacht had realized its position was untenable, and had made the decision to withdraw from the country rather than fight to the last man and face being surrounded by the might of the Red Army. With Romania in Russian hands following its capitulation and changing of sides, and with the Red Army in control of the Ukraine following the Lvov-Sandomierz Offensive, the Russians were advancing westward, toward Warsaw, the Polish capital, and East Prussia, the first swathe of German land that would be taken by the Russians.

In March 1943, disgruntled Jews living in the Jewish ghetto in Warsaw learned they were to be relocated to the death camp at Auschwitz, prompting a ghetto-wide uprising. Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, as it came to be known, was put down brutally by the Wehrmacht, along with assistance from the SS, yet the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising would not be the last act of resistance committed in the Polish capital. In October 1944, the Polish Home Army, an underground resistance movement spearheaded by General Tadeusz Komorowski, launched an uprising against their German occupiers. The uprising had been months in planning, and had the support of the Polish government-in-exile in London. Considering the majority of able-bodied Polish men had been committed to assisting the Allies in western and southern Europe (Monte Cassino was finally taken in May 1944 by Polish troops), the Poles launched the uprising with any able-bodied person they could find, from all age groups. The uprising was designed to coincide with the advance of the Red Army, with the Polish believing the Red Army would come to their aid as the uprising got underway, yet that was not the case. The Russians had been on a nonstop advance in Poland and the Baltic States for nearly three months when the uprising got underway, and the Russians attributed this exhaustion due to the Red Army’s nonstop advance to why it halted short of Warsaw. The Poles knew full well they were not properly equipped to combat the Germans in Warsaw for a long period of time, virtually any period of time over one month, and as it was soon realized the Russians had halted short of Warsaw, the Poles realized what had happened. Heinrich Himmler stepped in with the SS, and mopped up, crushing the rebellion, and executing those captured who were responsible for its construction. As the Poles were killed at the hands of the Germans as the Russians watched across the river Vistula, the Russians opened a siege of Budapest, the capital of Hungary, which they had swung around. The city, actually two cities, Buda and Pest, which sat across the river Danube from one another, was defended by crack infantry of the 6th SS Panzer Army under the command of General Sepp Dietrich, which had been forced to the front in Hungary in spite of the fact they had just suffered a staggering defeat in the Ardennes Forest against the Allies. The siege opened in late December, and after over a month of brutal street fighting, often hand to hand, the battle closed in mid-February 1945. The fighting in Budapest and the Russian advance into southern Germany, coupled with the Russian advance into eastern Austria, sealed Germany’s fate. As the last of the German forces in Budapest was killed by the onslaught of the Red Army, and after the Red Army finally entered Warsaw and took the city in late January 1945, slaughtering German troops in the very same ruins utilized by the Polish Home Army to combat the forces of the Reich, the Red Army finally reached the river Oder in early February 1945, just as Budapest fell. With Hungary, Yugoslavia, Poland, the Baltic States, East Prussia, and Romania in Russian hands, Germany was the final piece to the puzzle of victory. After fording the river Oder and entering Germany in April. The following month, the Prague Offensive opened in Czechoslovakia, finally liberating the country from Nazi control. As the first Russian forces crossed the Oder into Germany in mid-spring 1945, the Allies had already crossed the Rhine in force the previous month, and were advancing almost unhindered across the vast expanses of Germany. The Reich was entering its final days as the western Allies and Russians closed in, bearing down on Berlin, the dark heart of the German Reich.

On April 20th, 1945, Adolf Hitler’s 56th birthday, the first Katyusha rockets rained down on Berlin. Within a week, Hitler would be dead. The Fuehrer had entered what was known as the Fuehrerbunker, a formidable network of subterranean passages beneath the Reich Chancellery Building designed to maintain the life of the Reich, even when the Red Army was closing its heart in a vice. His descent into darkness had been executed in January 1945 following the defeat in the Ardennes and the loss of Warsaw, and he had been seen little since, his last trip being taken on April 20th, 1945, to award child soldiers of the Hitlerjugend, the fanatical SS organization that trained men, in some cases as young as fifteen or sixteen years of age, to become future SS officers, Iron Crosses, the highest German commendation. As the war came to Germany’s doorstep, the boys of the Hitler Youth were called upon to serve the Reich, even in their young years. Men between the ages of 16 and 60 were drafted to defend the Reich, along with the sick and weak. Josef Goebbels, the Reichminister of propaganda and one of Hitler’s inner circle, along with Martin Bormann and Alfred Jodl joined Hitler in the dark confines of the Fuehrerbunker as his final descent into madness was executed. On April 20th, Himmler visited Hitler in the bunker, and left for his home in Hamburg shortly after. It would be the last the two saw of one another. Hitler had been driven slowly insane, some attributing this to Parkinson’s, multiple-sclerosis, or syphilis. His left arm developed a very noticeable quiver, and he was forced to hold onto it with his right arm to prevent it from being seen. He had developed a case of almost hysterical blindness, brought on by increased paranoia and compounding stress as the war progressed. Following the July 20th plot on his life, he could no longer trust even those in his High Command, men who had sworn an oath to defend Hitler and the Reich to their last breath. If he could not trust even them, who could he trust? After the Allied victories in Italy, France, Belgium, and even as they entered Germany, along with the Russian victories in Eastern Europe throughout 1944, the war had been brought to Hitler, and his beleaguered, outnumbered, and outgunned men could do very little to stop it. Allied bombing, executed by the American 8th Air Force in England and 15th Air Force in Italy, and the Royal Air Force’s Bomber Command, further exacerbated the problem by damaging German industry needed to fight the war and combat an enemy who was getting only closer to Berlin. The final defensive line before Berlin, at Seelow Heights, defended by the 9th Army, part of General Gotthard Heinrici’s Army Group Vistula (pieced together from what was left of Army Group A and Army Group Center after Operation Bagration. Army Group South had been renamed Army Group Center, Army Group Center had been renamed Army Group North, and Army Group North had been renamed Army Group Courland, after the Courland region of the Baltic States it was to defend) was shattered, the Russians opening a 56-mile highway to Berlin. On the 21st, the first Russian troops of Marshall of the Soviet Union Georgy Zhukov’s 1st Belorussian Front broke through Seelow Heights, and within days, they were in Berlin, and the city was almost completely surrounded by Russian troops. In January 1945, General Dwight Eisenhower, the Supreme Allied commander, had handed the Russians Berlin primarily due to the fact that his men could never make it there in time, and the Russians were just a handful of miles from the capital. Winston Churchill, the British Prime Minister, had cautioned Eisenhower that his men needed to take as much of western Germany as possible before the Russians took Berlin. As the Russians closed in on the city against a resistance composed of the old, the young, the weak, and the sick, a motley crew of citizen soldiers fighting alongside men of the elite Waffen- and Leibstandarte-SS, Hitler placed his final dreams of preventing Berlin from falling into Russian hands on General Felix Steiner in a last ditch attempt of breaking through the Russian salient at Seelow in order to save his city from annihilation, and on April 22nd, 1945, as Russian forces bore down on Berlin, Hitler was told the offensive had not been launched, and the Russians were finally in Berlin. Hitler ordered everyone except a handful of officers, including Wilhelm Keitel, the commander of the Army, Alfred Jodl, the Chief of Operations Staff of the Army, Hans Krebs, Chief of Staff for the Army, and Wilhelm Burgdorf, one of the few generals who had joined Hitler in his final days, to leave. After their departure, Hitler shouted at his officers and blamed the ineptness of his generals, and cited their treasonous acts and disobeying orders, as to what had caused Germany to lose the war. The Russians had broken through Seelow Heights on April 21st after Hitler had ordered a counterattack against Russian positions outside the area, but the attack had not been orchestrated, and the Russians had broken through, winning a pathway to Berlin that they fully exploited. For the first time in almost five and a half years, Hitler announced the war was over for Germany, and stated he would remain in the dying capital until the end and commit suicide when he felt everything he could have done to save the Reich was done. Hitler had been in denial about how badly he was losing the war until it was already too late, admitting his failure as the first Russian troops entered the city. The day after the meeting in which he announced his ultimate failure, the Russians surrounded Berlin.

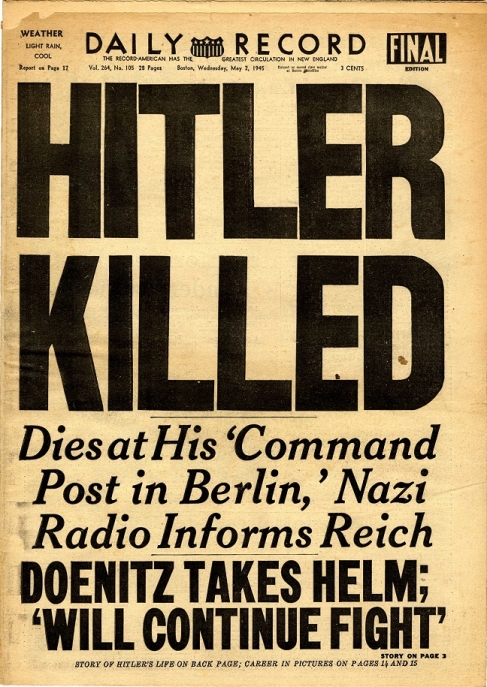

As outnumbered and outgunned German troops fought to the last man in Berlin, and as German troops surrendered in droves, the largest being a mass surrender of over 300,000 German troops in the Ruhr Pocket, to the Western Allies, Hitler remained in the Fuehrerbunker, listening to the artillery that shook dust loose from the ceiling and as bullets flew that killed what was left of his shattered dream of a thousand year Reich. Hitler had drafted a plan in which, if he were dead or compromised, Hermann Goering, one of the members of his inner circle, would assume command of Germany. As Russian soldiers slaughtered German troops above the Fuehrerbunker, Hitler received a telegram from Berchtesgaden, on the German-Austrian border in the Alps, where both Hitler and Goering had a personal residence. The telegram asked if Goering could assume leadership of Germany and even set an end date for when he would assume leadership if Hitler did not respond, considering Hitler was thoroughly compromised, not only in the sense that any escape from the Russians was impossible, yet also due to his now obviously frayed nerves and shattered mentality. Hitler had been driven slowly insane, and with his paranoia and fears of treachery now prevalent in his mind since the July 20th plot, after he read the telegram, he went on a rage, ordering Goering to be arrested. The wording of the letter was almost completely harmless in its approach, yet Hitler would not accept even the slightest inklings toward treason or mutiny. As the fighting in Berlin raged, British troops closed in on Hamburg, and the personal residence of Heinrich Himmler. As they did so, in April, the British liberated the concentration camp at Bergen-Belsen, just days after American forces liberated the camp at Dachau. Earlier that year, in January 1945, the Russians had liberated Auschwitz. It was discovered that the men defending the camps were SS, men under the command of Heinrich Himmler, and when Himmler realized the British were closing in, he attempted to surrender himself to the British, fearing capture by the Russians instead would be far worse. The British had just discovered what men under his command had done, and promptly refused his surrender, broadcasting the attempted act over radio on BBC. In Berlin, in the Fuehrerbunker, all communications by telephone and telegram had been severed by the Russians, and Hitler and his command staff only knew what was going on outside the city by what they could hear over radio, and on April 28th, 1945, they learned of Himmler’s attempted surrender. Hermann Fegelein, Himmler’s representative to Hitler’s Berlin headquarters, was dragged out of the Fuehrerbunker and shot, and Hitler ordered for the creation of a military tribunal to sentence Himmler after he was arrested. As is obvious, none of these orders were carried out. At midnight on April 29th, 1945, Hitler was married to Eva Braun, his long-time mistress and third cousin. The two had sustained a brief love affair as the war progressed, and finally wed in the bunker as the Russians ripped the city limb from limb. Shortly thereafter, Hitler and his personal secretary, Traudl Junge, authored his last will and testament. Due to his near-lost vision and uncontrollable spasms in his arms, he could not author it himself, and so Junge acted as a scribe. The documents contained who would succeed Hitler after his death, as well as who would take which positions after they were vacated by the sudden change in command. Goering was stripped of all government titles, along with Himmler, for their alleged treachery, and Goebbels was named to succeed Hitler as chancellor of the Reich. Admiral Karl Doenitz, commander of the Navy and father of Germany’s U-boat armada, would succeed Goebbels. Hitler also ordered that after he committed suicide, he wanted his body burned. The last detail was included after news reached Hitler of the capture and execution of Benito Mussolini on the 29th by Italian partisans. Mussolini had been attempting to flee the Salo Republic with his mistress, Clara Petacci, and rendezvous with a large contingent of loyal Blackshirts when the two were intercepted by partisans. They were taken to a field, gunned down, and their bodies were strung up by their ankles in Milan. The citizens of Milan spit on the bodies and threw garbage, and after Hitler learned of this, he became strengthened in his resolve not to be captured, and ordered his body burned so that the Russians could not do the same to him as the Italians had done to Mussolini. On April 30th, 1945, Hitler fed his German shepherd, Blondie, cyanide, and shortly thereafter shot himself. His body was taken outside the bunker and burned along with Eva Braun, who had taken cyanide as well. On May 1st, 1945, Josef Goebbels succeeded Hitler as chancellor of Germany, and within a day, he too would be dead. Goebbels acquired cyanide capsules from Doctor Werner Haase, the practicing physician the bunker who had replaced Theodor Morell, Hitler’s original physician. On the 22nd, Hitler dismissed Morell, and Haase succeeded him, giving Goebbels the cyanide capsules that he would then distribute to his wife, Magda, himself, and their six children. The bodies of the Goebbels family were taken outside and burned as well, yet the burning had not been nearly as successful as it had been with Hitler and Braun’s corpses. On the night of May 1st, 1945, Martin Bormann and several others, with the Fuehrerbunker now devoid of real leadership, attempted to flee the surrounded, battered capital. Many reports that Bormann had survived and had been helped out of the country to Argentina, where many Nazis fled after the war due to friendly relations with Argentina’s dictator Juan Peron, yet in the 1990s, his body was discovered under a parking lot and positively identified by DNA testing. He had never escaped. On May 2nd, 1945, the capital fell to the Russians, and on May 8th, 1945, Doenitz signed the German surrender, with it taking effect on the 9th. The war in Europe was over, and the Cold War was just beginning.

Although the most popular and accepted theory regarding Hitler’s death is that he shot himself and had his body burned, there are numerous other theories regarding his death or escape, considering no one has ever found a piece of his body. A skull fragment with a bullet hole through it was found by the Russians and held in a museum, with the Russians claiming it was that of Hitler, but was later identified to be that a forty-year-old woman killed during the battle. The lack of proper communication between the Russian and Allied communities after the war, and with the Russians claiming that any piece of human bone found was that of Hitler’s led to a massive discrepancy in what was real and what was not. To this day, Hitler’s body has never been found, although the most popular theory is that of Hitler shooting himself and having his body burned, considering that was what he stated he would do and wrote into his will. On the day of Hitler’s death, April 30th, eye witnesses also reported seeing Hitler personal Junkers Ju-52 transport landing in Madrid, Spain, en route to Argentina, yet this has never been confirmed. The organization Odessa, which existed for several years after the war to assist former Nazis in escaping to South America, where many governments were sympathetic to the Nazi cause, was credited with allowing Hitler to escape, yet this would have been impossible with the amount of Russian soldiers in the city during the battle. As the Russians closed in on Berlin and the Western Allies reached the river Elbe in May 1945, the war had finally been brought to a close after nearly five and a half years of combat, with American and Russian troops rounding up as many German rocket and weapon scientists as they could before the other, such as the American Operations Paperclip and Overcast. In the Pacific, it would rage on for nearly four months, until two super weapons were dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, ushering in a period of splitting the atom, and adding a particularly fearful tone to the period between 1945 and 1991: the Cold War.

Leave a comment